| |

|

The following scene from "Hooves and the Hovel of Abdel Jameela" by Saladin Ahmed does a wonderful job of pulling the reader into the story by using senses other than just sight. Her voice is more beautiful than any woman’s. And there is the powerful smell of jasmine and clove. A nightingale sings perfumed words at me while my mind’s eye burns with horrors that would make the Almighty turn away.

If fear did not hold your tongue, you would ask what I am. Men have called my people by many names—ghoul, demon. Does a word matter so very much? What I am, learned one, is Abdel Jameela’s wife.

For long moments I don’t speak. If I don’t speak, this nightmare will end. I will wake in Baghdad, or Beit Zujaaj. But I don’t wake.

She speaks again, and I cover my ears, though the sound is beauty itself.

The words you hear come not from my mouth, and you do not hear them with your ears. I ask you to listen with your mind and your heart. We will die, my husband and I, if you will not lend us your skill. Have you, learned one, never needed to be something other that what you are?

Cinnamon scent and the sound of an oasis wind come to me. The following excerpt from "The Children of the Shark God" by Peter S. Beagle introduces us to the protagonist quickly, but in a way that makes us care about what happens to her.Mirali’s parents were already aging when she was born, and had long since given up the hope of ever having a child — indeed, her name meant "the long-desired one." Her father had been crippled when the mast of his boat snapped during a storm and crushed his leg, falling on him, and if it had not been for their daughter the old couple’s lives would have been hard indeed. Mirali could not go out with the fishing fleet herself, of course — as she greatly wished to do, having loved the sea from her earliest memory — but she did every kind of work for any number of island families, whether cleaning houses, marketing, minding young children, or even assisting the midwife when a birthing was difficult or there were simply too many babies coming at the same time. She was equally known as a seamstress, and also as a cook for special feasts; nor was there anyone who could mend a pandanus-leaf thatching as quickly as she, though this is generally man’s work. No drop of rain ever penetrated any pandanus roof that came under Mirali’s hands.

Nor did she complain of her labors, for she was very proud of being able to care for her mother and father as a son would have done. Because of this, she was much admired and respected in the village, and young men came courting just as though she were a great beauty. Which she was not, being small and somewhat square-made, with straight brows — considered unlucky by most — and hips that gave no promise of a large family. But she had kind eyes, deep-set under those regrettable brows, and hair as black and thick as that of any woman on the island. Many, indeed, envied her; but of that Mirali knew nothing. She had no time for envy herself, nor for young men, either. The following excerpt from "Shadow Children" by Heather Brewer sends a chill down my spine every time I read it. Through sheer courage and selflessness, teen Dax has just saved his six year-old brother Jon from the clutches of shadow creatures in Jon's closet.She turned back to Dax with a concerned look on her face. "Dax? Is everything okay? We were so scared that something happened to you both."

Dax slowly nodded his head, even though everything was about as far from okay as it could get, and looked from the closet to the sunny day outside. Out the window, he could see the neighbor kids playing soccer. To any onlooker, it would seem like an ordinary, normal day.

He turned back to his mom and released a relieved sigh. "Yeah, mom. Everything's fine. We just—"

As she turned around, Jon peered over his mother's shoulder at Dax, who froze. Jon smiled and offered a wave.

Shadows lurked in his eyes—the darkest that Dax had ever seen. In this scene from "Frost Child" by Gillian Philip, the horror takes a moment to sink in, as the reader realizes what the child witch is feeding her newly-tamed water horse."He’s very beautiful," I smiled. "Make sure he’s fully tame before you bring him near the dun."

"Of course I will. Thank you, Griogair!" She bent her head to the kelpie again, crooning, and reached for her pouch, drawing out a small chunk of meat. The creature shifted its head to take it delicately from her hand, gulping it down before taking her second offering. She stroked it as she fed it, caressing its cheekbone, its neck, its gills.

I don't know why the first shiver of cold certainty rippled across my skin; perhaps it was her contentment, the utter obliteration of her grief; perhaps it was the realisation that she and her little bow had graduated to bigger game. The chunks of flesh she fed it were torn from something far larger than a pigeon, and as the kelpie nickered, peeling back its upper lip to sniff for more treats, I saw tiny threads of woven fabric caught on its canine teeth.

In the following excerpt from "The Adventures of Lightning Merriemouse-Jones" by Nancy and Belle Holder, the voice and sentence length quickly convey the time period and lighter tone of this comic horror.To begin at the beginning:

That would be instructive, but rather dull; and so we will tell you, Gentle Reader, that the intrepid Miss Merriemouse-Jones was born in 1880, a wee pup to parents who had no idea that she was destined for greatness. Protective and loving, they encouraged her to find her happiness in the environs of home—running the squeaky wheel in the nursery cage, gnawing upon whatever might sharpen her pearlescent teeth, and wrinkling her tiny pink nose most adorably when vexed.

During her girlhood, Lightning was seldom vexed. She lived agreeably in her parents' well-appointed and fashionable abode, a hole in the wall located in the chamber of the human daughter of the house, one Maria Louisa Summerfield, whose mother was a tempestuous Spanish painter of some repute, and whose father owned a bank.

Of course, interesting characters and engaging dialog are important, but writing gripping action scenes is a skill all its own. A skill that has been mastered by Jim Butcher, as shown in the following excerpt from "Even Hand".The fomor's creatures exploded into the hallway on a storm of frenzied roars. I couldn't make out many details. They seemed to have been put together on the chassis of a gorilla. Their heads were squashed, ugly-looking things, with wide-gaping mouths full of shark-like teeth. The sounds they made were deep, with a frenzied edge of madness, and they piled into the corridor in a wave of massive muscle.

"Steady," I murmured.

The creatures lurched as they moved, like cheap toys that had not been assembled properly, but they were fast, for all of that. More and more of them flooded into the hallway, and their charge was gaining mass and momentum.

"Steady," I murmured.

Hendricks grunted. There were no words in it, but he meant, I know.

The wave of fomorian beings got close enough that I could see the patches of mold clumping their fur, and tendrils of mildew growing upon their exposed skin.

"Fire," I said.

Hendricks and I opened up.

The new military AA-12 automatic shotguns are not the hunting weapons I first handled in my patriotically delusional youth. They are fully automatic weapons with large circular drums that rather resembled the old Tommy guns made iconic by my business predecessors in Chicago.

One pulls the trigger and shell after shell slams through the weapon. A steel target hit by bursts from an AA-12 very rapidly comes to resemble a screen door.

And we had two of them.

The slaughter was indescribable. It swept like a great broom down that hallway, tearing and shredding flesh, splattering blood on the walls and painting them most of the way to the ceiling. Behind me, Gard stood ready with a heavy-caliber big-game rifle, calmly gunning down any creature that seemed to be reluctant to die before it could reach our defensive point. We piled the bodies so deep that the corpses formed a barrier to our weapons.

The following excerpt from Jane Yolen's "A Knot of Toads" describes a scene so vividly that the reader feels immersed in it.The evening was drawing in slowly, but there was otherwise a soft feel in the air, unusual for the middle of March. The East Neuk is like that—one minute still and the next a flanny wind rising.

I headed east along the coastal path, my guide the stone head of the windmill with its narrow, ruined vanes lording it over the flat land. Perhaps sentiment was leading me there, the memory of that adolescent kiss that Alec had given me, so wonderfully innocent and full of desire at the same time. Perhaps I just wanted a short, pleasant walk to the old salt pans. I don’t know why I went that way. It was almost as if I were being called there.

For a moment I turned back and looked at the town behind me which showed, from this side, how precariously the houses perch on the rocks, like gannets nesting on the Bass.

Then I turned again and took the walk slowly; it was still only ten or fifteen minutes to the windmill from the town. No boats sailed on the Firth today. I could not spot the large yacht so it must have been in its berth. And the air was so clear, I could see the Bass and the May with equal distinction. How often I’d come to this place as a child. I probably could still walk to it barefooted and without stumbling, even in the blackest night. The body has a memory of its own.

Halfway there, a solitary curlew flew up before me and as I watched it flap away, I thought how the townsfolk would have cringed at the sight, for the bird was thought to bring bad luck, carrying away the spirits of the wicked at nightfall.

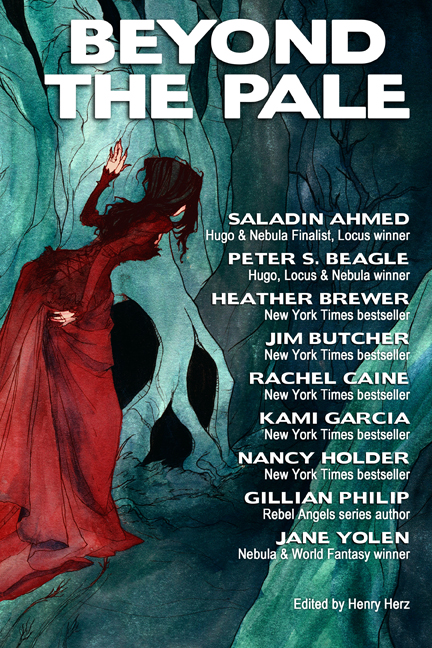

Get your copy of Beyond the Pale.

|

|

|